A brand-new initiative to develop a child and adolescent psych unit at Southwestern Medical Center in Bennington is already off on the wrong foot when it comes to input from psychiatric survivors and their families. Likewise for an initiative to develop an urgent care program in a collaboration between the Howard Center and the University of Vermont Medical Center.

Repeatedly, the federal directive for “mental health care that is consumer and family-driven” is misunderstood in two ways: 1) that it is only talking about a person’s own care, not the system as a whole; or 2) that consumer-driven means getting some input on a plan that is already underway (or sometimes, already nearly complete).

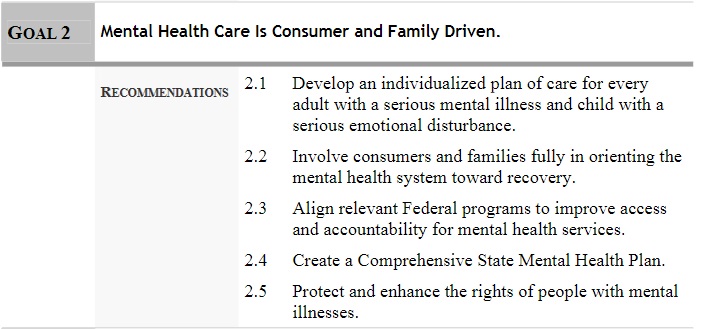

If you go way back to 2003 and President George Bush’s final report on “Achieving the Promise” for transforming mental health care in America, you find a very clear description.

It says: “Consumers of mental health care must stand at the center of the system of care… In a consumer and family-driven system… (t)heir needs and preferences drive the policy and financing decisions that affect them… Local, state, and federal authorities must encourage consumers and families to participate in planning and evaluating treatment and support services. The direct participation of consumers and families… is a priority.”

This is about the system, not about individual care. This is about driving policy and about planning the programs, not about giving generic advance input or involvement in discussions after key decisions have been made.

The Department of Mental Health is now in the second stage of the planning for the new hospital unit in Bennington. It sent out a request for proposals from hospitals without involving families in what the criteria should be. DMH has now signed a statefunded contract for Southwestern Medical Center to conduct a feasibility study without family input into what such a study should include. Although it was good to hear that the hospital may bring stakeholders into the feasibility review, that was its initiative, not a requirement from DMH.

DMH also participated in a meeting of various interested providers and community members about possible development of an urgent care center. The discussion failed to include any survivor voices. When the Howard Center began refining the early plans, they also did not bring any survivors or peer support workers into the discussion, saying it was still premature.

The whole system is still stuck in the tired old concept of asking for input after the policy decisions are made, instead of having survivors, peers and families be a part of that decision-making. These proposals may all be terrific. It may be that we all support them. But DMH is in the driver’s seat for choosing the priorities and implementation. We were most definitely not in “the center of the system of care.” Has everyone forgotten that it is supposed to be, “Nothing About Us Without Us”?

Fortunately, it is still early enough in the work to correct course and bring us on board. Survivors can help review proposals, even if not involved in drafting the original requests for them, thereby helping to prioritize which plans are best, and what next steps should happen. Contracts must require our inclusion in the actual development of programs.

It’s time for us to be brought into the decision-making process if we are ever to “achieve the promise” of almost 20 years ago.