State Lags on Requirement To Divide Case Management from Services

MONTPELIER – In 2014, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services issued new regulations intended to protect Medicaid beneficiaries who receive care outside of institutional settings.

Vermont is still playing catch-up, which is frustrating advocates who have worried for years about a conflict of interest between agency case managers and the services their clients are eligible to receive.

A category of programs called “home- and community-based services” accounts for about $115 billion in annual Medicaid spending nationally.

In Vermont, under the administration of the Department of Mental Health and the Department of Disabilities, Aging, and Independent Living, they have five names: Choices for Care, Community Rehabilitation and Treatment, Developmental Disabilities Services Program, Intensive Home- and Community-Based Services, and Traumatic Brain Injury Program.

Through home- and community-based services, the state’s community mental health centers and specialized service agencies deliver care to Vermonters with psychiatric diagnoses and developmental and intellectual disabilities. But before they do, for each client, they perform an assessment of needs and design a plan to address them.

According to CMS, its new regulations require that part of the process to start taking place under a different roof. Under the updated rules, in order to avoid conflicts of interest, case managers cannot work for the same agency tasked with delivering the package of services that they’ve coordinated.

The federal regulators say that this revision relieves case managers of “possible pressure to steer the individual to their own organization.” They should instead offer clients “full freedom of choice of types of supports and services and individual providers” and be prepared to tackle “problems related to outcomes and quality,” which, as CMS points out, can be hard to do if the problems owe to “the performance of coworkers and colleagues within the same agency.”

This summer, CMS approved Vermont’s application for a five-year extension on its Global Commitment to Health waiver, the agreement that governs the state’s Medicaid program. In doing so, it conditioned that agreement upon Vermont’s willingness to enter compliance with its conflict-of-interest rules. Once CMS has okayed the state’s plan, it will appear within the waiver, on page 250, as Attachment Q.

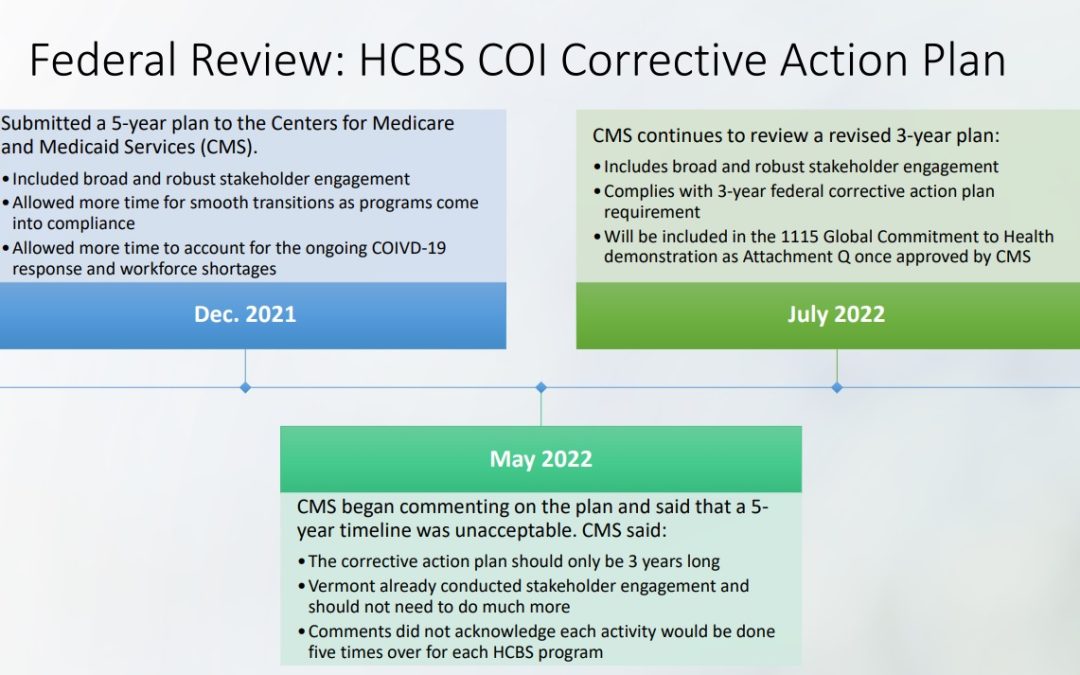

So far, the page sits blank. Last December, the Vermont Agency of Human Services proposed a five-year transition to conflict-free case management, as it’s called, but CMS rejected it and demanded a three-year timeline.

It hasn’t yet approved Vermont’s hastened corrective action plan, originally scheduled to begin its stakeholder engagement phase this past September with the assembly of an advisory committee of “consumers, providers, families, guardians, advocates, and other groups.”

But the state has continued to get ready. In November, AHS executed a contract for technical assistance. A long process of analysis will precede the actual implementation of the new system of case management, set to begin in 2025. A new stakeholder engagement plan is also being developed, and the process will begin after the plan is finalized, AHS indicated.

Until recently, Vermont hoped to achieve conflict-of-interest compliance simply by offering Medicaid beneficiaries the option of receiving case management separately from the provision of their home- and community-based services, but CMS let the state know last year that simply providing clients with an option wasn’t good enough.

The Vermont Center for Independent Living has been a longtime advocate for a move to conflict-free case management.

“It’s about people truly understanding all their different choices, and I think that we have had a history in Vermont where people aren’t always given all the information,” said Sarah Launderville, VCIL’s executive director.

“It’s not like the federal government said, ‘Here’s a new rule we want to see.’ It was people with disabilities nationally coming together and saying, ‘We want to see this happen,’” she added.

Kirsten Murphy, the executive director of the Vermont Developmental Disabilities Council, also expressed support for the change to address the conflicts of interest that she said do exist in Vermont’s system of care.

“People don’t have to receive their services from their regionally designated agency, but sometimes they don’t learn about that because it’s not in the interest of their regional agency to tell them that,” she observed.

Most states have already fully adopted conflict-free case management, but Vermont officials were initially reluctant to disentangle their “vertically integrated system,” as Murphy called it.

“We are by far the farthest behind,” she said. In her view, the creation of an “ombuds office” will be a key reform. The ombuds would investigate complaints by individuals who receive home- and community-based services.

An option the state could pursue to meet the federal requirements would be to contract with an organization to provide mandatory conflict-free case management throughout Vermont, or it could require each agency to find a third-party case management service of its own choosing.

The agencies themselves could provide reciprocal case management in one another’s geographic catchment areas, or some could transition exclusively to case management with others functioning exclusively as service providers. Other states offer examples, but so far, no one knows what will happen here.

That has made some people nervous, including Rutland Mental Health Services CEO Dick Courcelle.

“We’re still trying to understand what this really means because, in some cases, it makes no sense,” he opined. “Consider you’re going to your doctor, and your doctor diagnoses you with type-two diabetes, but your doctor says, ‘I am diagnosing you with diabetes, and we need to manage that diabetes. However, I cannot be the one to do that, so I’m going to refer you to someone else for your care.’ That’s sort of what this is.”

By Courcelle’s judgment, the service provider is in a better position than a third party to design a plan of care because the service provider knows “what can be delivered, what’s available, and how to arrange those services.”

He also wondered where funding for case management contractors would come from and whether cash-strapped community mental health centers would suffer financially under the new arrangement.

“You’re dealing with a system that is fragile and has been fragile for many years due to chronic underfunding,” he commented. “My assumption is that this is a zero-sum game. If the money has to go somewhere, it’s going to have to come from somewhere.”

Courcelle pointed out that Vermont’s community mental health centers don’t operate on a fee-for-service basis, so they don’t have an incentive to load up clients with unnecessary services.

“But the federal government tends to like a one-size-fits-all approach,” he said.

Where will the funding come from? It MUST come from federal dollars. Please watch world-renowned economist describing how such a national healthcare program should look: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lypnn9fLTVs We brain injury patients are not told what services and treatments are available to us and do not receive the care we need to meet our needs. -I didn’t even get a case manager after suffering a complex head injury including a moderate TBI, skull fractures, excruciating pain from facial fractures (trigeminal neuralgia), vision impairment from eye socket reconstruction, cognitive impairment (couldn’t comprehend written material), medically restricted from driving ( being the only adult in my home)… I clearly qualified as a complex patient case. Because I went without, I now suffer chronic issues that are difficult to treat. I found out through BI Peer Support groups that my peers were receiving care that I didn’t but should have. The medical literature describes BI care and services that I should have received. Why aren’t we? Actually, the most common question my peers ask is, “Who is coordinating my care?” There is so much more going on here: “conflict of interest” of case management than what this article describes, what our medical professionals and administrators will admit to. I was told “If I give you that referral, I’d have to give one to everyone.” Which says to me something is wrong here and we should investigate. I’ve a feeling it has to do with BI patients being “high cost patients”. What is the Mission of our healthcare system if not to meet the needs of our patients?